Good analysis of something that has received far less attention than the blackouts that resulted during the freeze. Which is interesting because the blackouts were the main cause of the water outages and resulting boil notices. And the fix here is relatively simple.

There generally are two sources of drinking water in Texas: underground wells and surface water, drawn from lakes, rivers and reservoirs. Both require pumps to move the water to storage tanks, purification plants and out to customers. And pumps require power.

In Houston, most drinking water is pulled from lakes Houston, Conroe and Livingston. The city’s issues during the freeze began at the Northeast Water Purification Plant, one of its three primary treatment facilities, where some of its generators did not turn on as designed that Monday, Feb. 15, Mayor Sylvester Turner said.

Internal reports, emails and texts obtained through public information requests by the Chronicle illuminate the problems. The emergency generator failures reduced the plant to about 20 or 30 percent of its normal capacity, according to situational reports from the Office of Emergency Management. This started a drop in pressure that workers struggled to halt.

NRG, which operates the generators, was supposed to be able to start them remotely. The generators were providing power to the grid when it collapsed, which caused them to trip offline, the company said. NRG employees taught Public Works officials how to reset them by phone. The city also had left two breakers in the wrong position prior to the storm, complicating the efforts to switch to back-up power, according to Houston Public Works. The power was restored three hours after it went out.

“Nearly lost the water system,” [Houston Public Works Director Carol] Haddock texted another city official later that afternoon, “but recovered it sort of.”

Meanwhile, eight of 40 city-operated generators failed at wells that pull water from underground. Though workers tested the generators monthly, checking their oil and fuel, Haddock told state lawmakers earlier this month the machines “were not prepared for starting in 12 degrees.”

One froze and was not functional again until temperatures rose. Another at the Katy Addicks well started initially before its supercharger failed. Others had mechanical issues related to the cold.

City staff chased outages with portable generators, recalled Phillip Goodwin, Houston Public Works’ regulatory compliance director. As power came on in one place, it would go out somewhere else in the system.

Water pressure in the city dropped, and by late Tuesday Houston officials saw a few readings below the state-mandated levels.

Haddock texted Turner at 8:13 p.m.: “I can tell you we are doing everything humanly possible.”

Some 13 hours later, Turner announced a boil water advisory was in effect, per Texas Commission on Environmental Quality requirements when water pressure drops too low.

It would be four days before the water was declared safe to drink. Dallas never needed a boil notice; the advisories in San Antonio and Austin lasted longer than Houston’s.

Turner said the bottom line is that the generators did not work as intended. He has instructed his departments to review what went wrong and build more “resiliency and redundancy” into the system.

“When you have power outages of that magnitude, it’s going to impact your systems across the board,” Turner said. “We have to put ourselves in the best position to prevent it from reoccurring, or at least at that magnitude.”

[…]

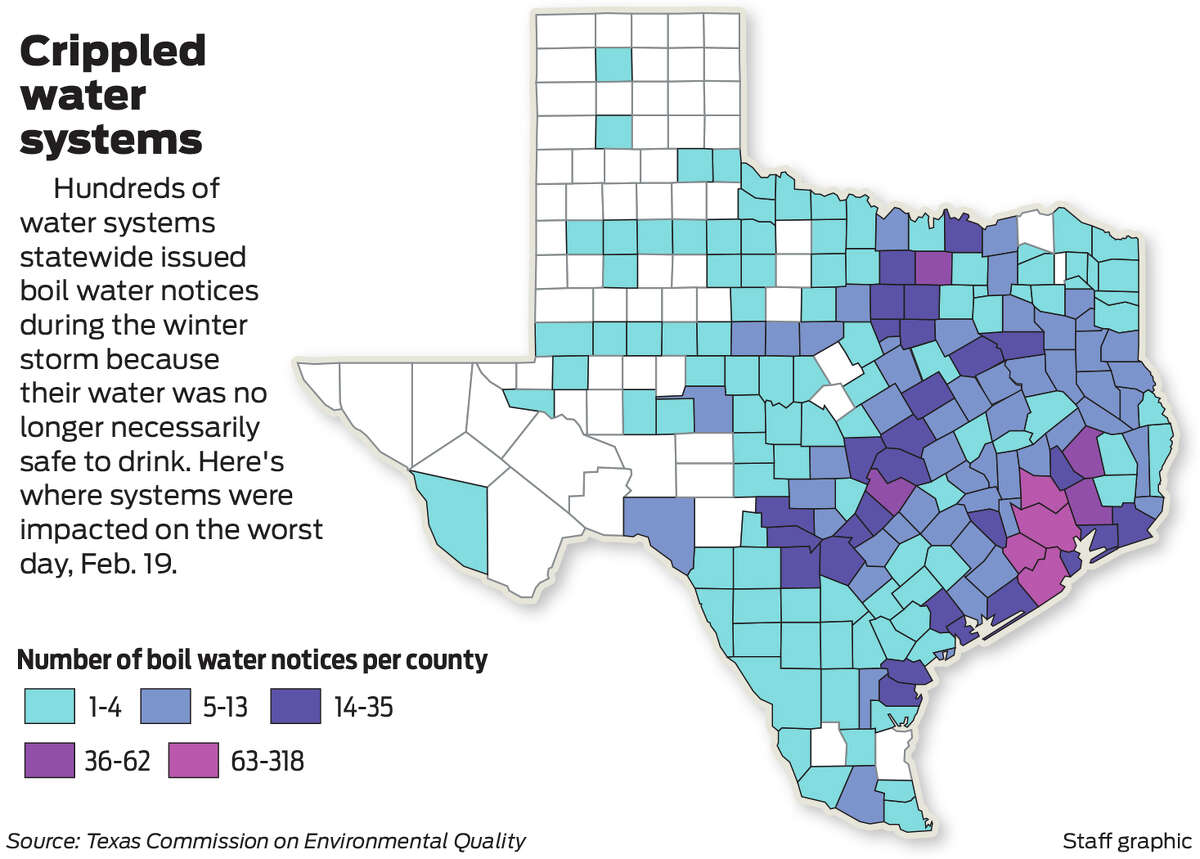

At the peak Friday, more than 1,800 of some 7,000 public water systems were under boil water advisories. Hurricane Harvey, by comparison, prompted some 200 systems to issue boil advisories, said TCEQ Executive Director Toby Baker. Houston was not one of them.

The TCEQ, which monitors boil notices and provides emergency assistance, plans to survey and hold roundtables with local providers to figure out what went wrong. They are forming a group to look at helping water systems get listed as critical infrastructure with electricity providers, among other issues.

Public Utility Commission rules say water facilities may be defined as “critical load” like hospitals, but the water utility must notify its electricity provider and be deemed eligible.

I certainly would have thought that water systems would be considered critical infrastructure. It would have saved a lot of trouble if the water treatment plants around the state had not lost power during the freeze. That might have caused more homes to lose power, perhaps, but if we’re forcing the power plants to weatherize then maybe that will be less of an issue. Requiring backup generators and a regular schedule for testing and maintaining them would also help. HB2275 would create a grant fund for infrastructure fixes – there may of course be some federal money coming as well, but we can’t count on that just yet – and I guess it’s up to the TCEQ to decide if water systems are “critical infrastructure” or not.

I mean, look, most of us were able to get by for a couple of days with the boil notices and maybe using melted snow as flush water. We won’t have the latter during a summer power-and-water outage, but never mind that for now. All I’m saying is that for a state that loves to brag about luring businesses here, this is some bad advertising for us. We have plenty of other challenges right now, many of them being perpetuated by the Lege. We should try not to add to them.

“I certainly would have thought that water systems would be considered critical infrastructure.”

I would also have thought that. That’s what we’ve always been told…..hospitals, fire and police, water and sewer plants…..those are critical. Apparently not. Hopefully, the Coldpocalypse will result in making sure we codify that they are deemed essential, as are the pipeline compressor stations.

One thing the article didn’t touch on, is the phenomenon of the City of Houston and Harris County trying to get surrounding cities and municipal districts hooked on City of Houston surface water from Lake Houston. They’ve kind of sold themselves into being the supplier of record for several surrounding areas. This is OK, I guess, until there’s a problem. When the CoH couldn’t deliver, suddenly all those who gave up on self sufficiency with their own wells had a problem, too.

I’m not sure what to do about this, I get that subsidence may be a real issue in places, but maybe those surrounding water systems should be focusing on at least having the well capacity to produce all their own water. It’s fine to buy the CoH surface water, but dependency isn’t a good thing.