There are a lot of other exonerations that happen around the country, for crimes major and minor, that don’t involve DNA.

In September 2006, [Corey] Love was charged by Houston police with possession of between one and four grams of cocaine, a felony. He was 20 years old and indigent.

He had two choices when he made his first appearance before a judge: Stay in jail waiting for laboratory tests to confirm the substance found on him was cocaine, or accept the prosecutor’s offer to plead guilty to a lesser charge, do his time in state jail and go home.

He chose the latter, received a credit of two days for every day served, and was released on Dec. 23, 2006. Six days later, Love was arrested and charged with robbing someone at the barrel of a BB gun, to which he pleaded guilty and was sentenced to three years in state prison.

In December 2012, the Houston Police Department crime lab finally got around to testing the substance taken from Love. It wasn’t cocaine. And it weighed less than 1 gram, which means that, even had he been carrying cocaine, Love would have faced a lesser charge in the first place.

The Harris County District Attorney’s Office notified the trial court, which appointed attorney Tom Moran to file a writ of habeas corpus on Love’s behalf. It was granted in June last year. Love’s conviction was vacated, and he was declared innocent.

That bit of good news likely hasn’t reached Love – neither Moran nor an investigator from the district attorney’s office has been able to find him to tell him.

“He has no clue,” Moran said. “I have no idea where he’s at. He was out of Louisiana. I checked with the Louisiana prison system but couldn’t find him.”

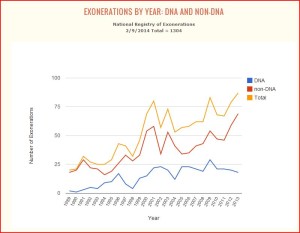

Nationally, the registry reported that the number of exonerations in 2013 based on DNA testing continued to decline and non-DNA exonerations were on the rise.

Nearly a third of the exonerations last year involved cases in which no crime had occurred. Fifteen individuals were declared innocent of crimes to which they had pleaded guilty but did not commit.

Seven of those cases, including Love’s, were in Harris and Montgomery counties, and six of them involved convictions for drug possession that were overturned after crime lab analysis determined no drugs were involved.

All seven defendants were convicted after accepting plea bargains, which is how the vast majority of convictions in the country’s federal and state courts are obtained – 97 percent of federal convictions and 95 percent of state convictions.

Grits was on this last week. The registry in question is the National Registry of Exonerations, which is a joint project of the University of Michigan Law School and the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University School of Law. You can see their report here; the embedded graph is from this page. The thing to keep in mind here is that Corey Love spent about three months in jail for something that wasn’t actually a crime. His is an extreme case, but there are a lot of people in our county jails like him, people who couldn’t make bail and wound up pleading to something so they could get their ordeal over with. We spend a lot of money on people like that, for no good purpose. We also spend a lot of money fighting to keep from re-examining the evidence in cases where strong doubt exists about the integrity of a conviction. There’s an awful lot more that we could be doing here, to either increase this number, or make it so that we don’t have to. The Atlantic has more.