Booming population growth plus greater upstream demands on their main water source equals thoughts of alternate water supplies.

By the time the Brazos bisects Brazoria County on its way to the Gulf of Mexico, it’s all but tapped out, unable to keep pace with new urban demands.

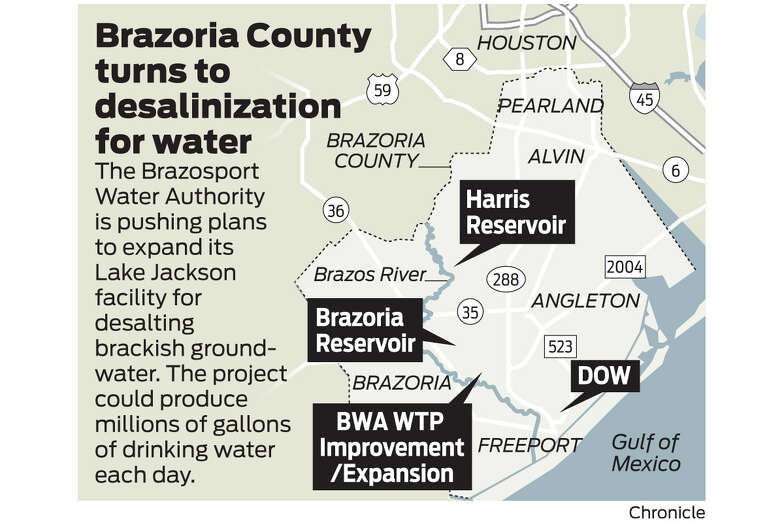

To firm up its water supply, a Brazoria County utility is moving quickly to pump from a massive saline aquifer beneath the Houston region’s surface. The Brazosport Water Authority’s roughly $60 million project – once the first phase is completed in 2017 – would convert millions of gallons of salty water into potable, or drinking, water each day.

The process, known as desalination, is used across Texas, mostly in the drier western half of the state. The Lake Jackson facility would be the first of its kind in greater Houston, which typically benefits from plentiful rain and full reservoirs. The city of Houston, in particular, is planning to meet its long-term needs with surface water and reused wastewater.

“It’s a bad time for rivers in Texas, and we’re only going to see more demand for water,” said Ronnie Woodruff, general manager of the Brazosport Water Authority, which has relied on the Brazos to provide water to seven cities and a massive chemical manufacturing complex. Brackish, or salty, groundwater “is a new, reliable source.”

Desalination is energy-intensive and expensive, but the stubborn drought, which now covers three-fourths of Texas, has infused the discussion about its possibilities with a jolt of urgency. Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst, for one, has instructed a state Senate committee to study how to expand the use of brackish water before the Legislature convenes in January.

Texas already has built 46 desalting plants for public-water needs. But there is the opportunity for manymore, considering the state holds about 2.7 billion acre-feet of brackish groundwater, the Texas Water Development Board estimates. That’s more than 150 times the amount of water the state uses annually.

For all its untapped potential, desalination of brackish water might not be a cure-all for a thirsty state, experts say. In addition to the cost, which will result in higher rates for customers, the desalting process requires disposal of the leftover brine in a way that avoids harming fresh water and the environment.

And it is still unclear how the push for brackish groundwater will impact the Houston region’s persistent problem with subsidence, the sinking of soils as water is pumped from underground. The geological condition can crack pavement and cause flooding. Several coastal communities are weaning themselves from groundwater because of the issue.

[…]

Some people worry that the project will become a high-tech monument to panic. The water authority should focus on conservation and the reuse of wastewater, said Mary Ruth Rhodenbaugh, a former Brazoria County commissioner who served on a local water-planning task force.

“God gives us water, and then He expects us to use our brains,” she said. “I’m not against brackish desalination, but I think we should be looking at other things first.”

I’ve written about desalinization a few times before. It’s an increasingly popular proposal around the state, as there’s plenty of potential supply. But it’s expensive, there are issues with what to do with the briny wastewater, and as noted no one really knows what the subsidence effect will be. No question, the best alternative is always conservation, and I don’t think that gets enough emphasis. If cities like San Antonio and El Paso can do it, surely Brazoria County can as well.