From City of Yes:

The sun came up Wednesday morning, but for many, no doubt, our proverbial American “shining city on a hill” had lost some of its luster. While the presidential election results have disappointed many city dwellers, the results in our actual, non-metaphorical cities show that the urban electorate also wanted something different—not a wholesale ideological shift, but leaders who actually take the problems of urban governance seriously.

Urban voters want to bring the shine back to their cities.

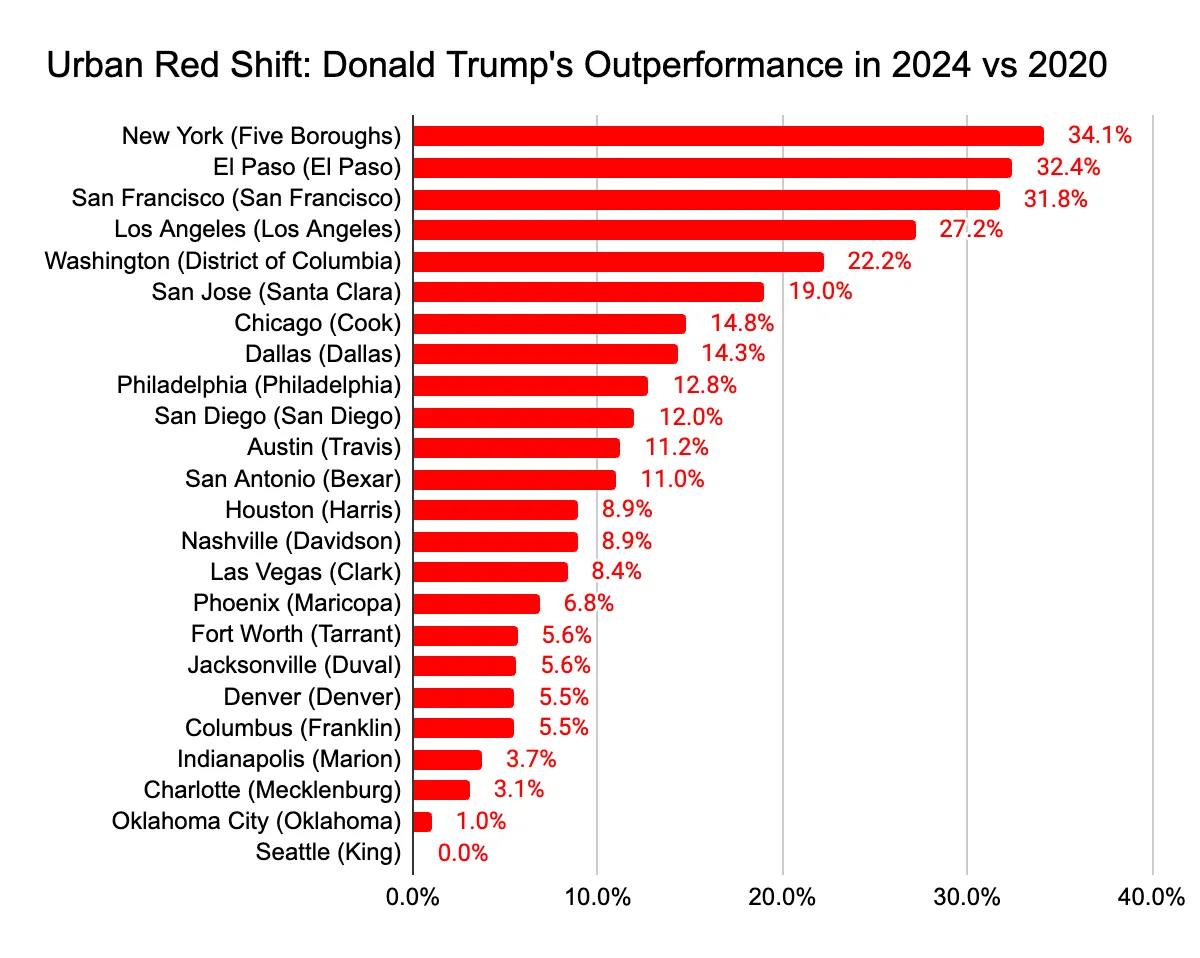

Many theories will be offered in the coming weeks to explain Kamala Harris’s decisive defeat, but the fact is that Donald Trump improved his performance over 2020 seemingly everywhere and with everyone—including in the densest, bluest cities. While Harris won most urban counties, the extent to which Trump outperformed his 2020 numbers is notable: he improved his share of the vote by 34% in New York City (nearly 70% in the Bronx!), 32% in San Francisco, 27% in Los Angeles, and 22% in Washington DC. In the chart below, you can see the red shift for the counties home to America’s 24 largest cities.

The rest is about a connection he draws between city governance and the Presidential vote, and you should read it and come to your own conclusions. My purpose is to talk about the chart, because my first reaction was “where in the world do you get an 8.9% increase for Trump in Harris County?” We’ve already shown that there was no Republican surge in Harris County. Trump’s raw vote total went up by a much more modest 2.78%, while his percentage of the vote went from 42.70% to 46.51%, an increase of 3.81 percentage points. That’s a real increase, though as noted yesterday it was much more about the drop in Democratic votes than anything else; I’m not going to relitigate that, go read that previous post for that argument.

Where that 8.9% figure comes from is that 46.51 is an 8.9% increase over 42.70 – as in, divide 3.81 into 42.70 and you get 0.089, which is to say 8.9%. I have a lot of problems with this type of comparison, which I went into in excruciating detail four years ago, when I encountered an even more painfully mis-informative chart. The issue here is that when you only compare percentages – or in this case, percentages of percentages – you are missing some important context, specifically the raw vote totals. This can lead to weird results at the extremes and sometimes the illusion of that you’re catching up when you’re actually falling farther behind. My earlier post gets into that, so please read it.

The bottom line for me is that you really have to include the vote totals to fully make sense of what happened here. I’ll do that in a second, but I also want to note that since we are comparing across years, it might also help to consider voter registration numbers as well. When comparing candidates from similar races in the same election, you know you’re dealing with the same pool of voters, so if Candidate A in Race A got more votes than Candidate B in Race B, you can say with some confidence that there were people who voted for Candidate A but not for Candidate B. But the fact that Donald Trump got 20K more votes in Harris County in 2024 than he did in 2020, it doesn’t follow that some people who voted for Joe Biden in 2020 must have voted for Trump in 2024. That’s because there are more voters in Harris County in 2024 than in 2020, and at least some of those 20K extra votes for Trump may have come from those new people.

That’s a lot of words, which I didn’t get into in the previous post, so let me give you another chart:

Year County Votes Voters Pct

==========================================

2020 Bexar 308,618 1,189,373 25.95%

2024 Bexar 336,260 1,295,580 25.95%

2020 Dallas 307,076 1,398,469 21.96%

2024 Dallas 319,319 1,467,410 21.76%

2020 El Paso 84,331 488,470 17.26%

2024 El Paso 104,966 521,945 20.12%

2020 Harris 700,630 2,480,522 28.25%

2024 Harris 720,046 2,693,055 26.74%

2020 Tarrant 409,741 1,212,524 33.79%

2024 Tarrant 425,650 1,309,456 32.51%

2020 Travis 161,337 854,577 18.88%

2024 Travis 170,613 921,313 18.52%

These are all the Texas counties covered in the City of Yes post. I included the voter registration figures to add that extra dimension. Yes, Trump got 20K more votes in Harris County in 2024 than he did in 2020 (actually 19,416, but whatever). But there were 213K more voters in Harris in 2024. Of the total universe of people who could have voted, Trump’s share actually decreased. That was also the case in Dallas, Tarrant, and Travis Counties.

Now for sure, my chart also shows some big problems for Democrats. There’s no sugarcoating what happened in El Paso, where the increase in Trump’s support is more than half the increase of new voters. Democrats’ hope for eventually reaching the summit in Texas rested (and still rests, let’s be clear) on their vote share steadily increasing in the big urban and suburban counties. If increases in voter registration in these places don’t translate to commensurate increases in the vote share, that’s a five-alarm fire. That Republicans held steady in Bexar County isn’t good either. Hell, the tiny decrease in Dallas is worrisome too. Honestly, the Harris and Tarrant numbers are the most reassuring from a Democratic perspective, and we already know we have big issues to confront in those places.

Indeed, I’m only showing this from a Republican perspective, since the hook of this post was the Trump increases. I didn’t do the same calculation for the Democratic share of the vote, but we already know that it would show an often-steeper drop in all of these counties, Harris especially. I mean, 200K more total voters, but 100K fewer Democratic votes? You don’t need a spreadsheet to know that’s bad news.

My point here, as before, is not that this isn’t a problem, it’s that it a different problem. Outside of El Paso (which, again, VERY BAD), Republicans didn’t gain vote share. Democrats lost vote share. It may be that some Biden voters from 2020 voted for Trump this time, but that’s swamped by the Biden voters who sat it out this year. The communication we need to have with the two groups are very different. I’m just trying to define the problem so that we can go forward as effectively as we can. Slate’s Henry Grabar has more.

Common ground: Kuff is a data man. Quality and persuasiveness of interpretation may indeed vary. – But a oneliner a day may not be enough to keep tedium away.

So here is more red-blue meat, attention span permitting:

WHY ELECTORATES CHANGE BETWEEN ELECTION CYCLES

Building on Kuff’s exposition, a wonk might additionally point out that 4 years worth of non-aborted fetuses who acquired citizenship when they saw the light at the end of the birth canal 18 years ago will affect the composition of the electorate in the present, as will the demise of older voters (statistically older in the aggregate) over the past four years. –> generational replacement. That’s in addition to in and out migration.

A certain polisci dude forget to mention that post-natal acquisition of citizenship (& resultant voter registration at age 18 and up) as well a small number of losses due to acquisition of felony status affects the collective size and composition of the electorate as well.

As an example, Oscar Stilley is back in federal prison in Okla for misstating his franchise eligibility status when suing the Arkansas Secretary of State on the abortion-related initiative there. He needed to do so for legal standing purposes, and he probably did it on purpose for a chance to relitigate the validity of his original conviction. Alas for him, it didn’t go too well.

Regardless of the merits of Stilley’s predicament (or Crystal Mason in Texas), there is a good normative argument to be made for letting prisoners vote: it would remove any partisan incentive to convict someone (or revoke conditional release or parole) to punish them for their policy activism (or for venting about public adulteration and corruption) or perhaps just for their known or likely past and future voting behavior: individually as well as collectively.

I’m using the Stilley case for didactic purposes only and note that the press release of th Arkansas AG disclaims any intent to punish Stilley for the substance of his abortion-related advocacy.

As for collectively, think about the large number of presumptively black Sugarland convict workers whose bodies were dug up a few years ago in the course of a school construction project. They had no way to complain about the treatment visited upon them while they were alive.